The Rationale for Rote Teaching

Why Teach by Rote?

During my years as an undergraduate piano major and a graduate piano pedagogy student, I spent many happy hours reviewing both current and historical piano methods. Method review projects were intriguing to me, and it is where I truly discovered my love for education, and in particular, curriculum development. When I met my co-author, Julie Knerr Hague, in graduate school, we discovered this interest was mutual, and we began our initial sketches for what would become Piano Safari.

As a result of our examination and use of various piano methods during college, we observed that the primary goal of most methods is not necessarily to teach children to play the piano. Instead, the goal of these methods is to teach children to read music notation at the piano. Because of this intense focus on reading, these methods might be compared to a grammar book intended to teach a student an ancient language.

Although a person may learn to read and write in Latin through the use of a grammar book, it will not be useful for learning to speak the language the way it sounded in the time of the Romans. In order to obtain a fluent grasp of the language, one would need to hear the language spoken and also practice speaking it. In the same way, a piano method with a primary focus on reading music notation may successfully guide students to read music notation, but it may not teach them to understand music aurally or to express it artistically.

Students may become disillusioned and uninspired when all the pieces in the book are at the same reading level with the same texture of single line melodies and simple rhythms. Most children have been exposed to complicated music since birth, and they are capable of playing more difficult music than they can read.

Teaching students by rote, or by imitation without extensive reference to the score, allows the development of listening skills, technique, memory, creativity, and artistry without the added complication of reading the notation. Music is an aural art, so students must learn music with their ears as well as with their eyes. A balance between pieces taught via notation and pieces taught by rote will help students deeply understand and fully express music.

Historical Precedent

There is historical precedent for rote teaching, although the term “rote” was not always used to describe this practice. The following quote from Claude Kenneson’s book, Musical Prodigies, provides an example of how Friedrich Wieck, father and teacher of the great pianist and composer Clara Schumann, taught this way during the early nineteenth century.

“During the first year of her instruction, he did not encourage her to learn to read music but rather to play by heart the small pieces he composed expressly for her use, piano music that encouraged the little girl to concentrate on physical position, musical phrasing, tone production, and familiarity with the keyboard, aspects that accounted for the superb facility and ease at the instrument that she demonstrated to the end of her life.” (Kenneson p. 79)

An additional example of Wieck’s style of teaching is found approximately one hundred years later. Again, although the word “rote” is not specifically used, the pedagogical approach developed by Shinichi Suzuki uses similar principles. In the book Nurtured by Love, he describes an illuminating moment when he realized that “all Japanese children speak Japanese.” Suzuki explains that language, or the “mother tongue,” is complicated in structure and sound, but children develop fluency simply by hearing it spoken in their surroundings. In a similar way, this language analogy implies that children grow naturally as musicians through early exposure in their environment.

Benefits of Teaching by Rote

Following are specific benefits students will receive when they learn rote pieces early in their piano study.

Motivation

Students are able to play aurally satisfying music from the beginning of study. This increases their motivation and promotes the desire to learn more music and continue studying their instrument. After all, why do most people study the piano? I think we would agree it is to make music. That’s really at the heart of it all. To make music! In the book A Piano Teacher’s Legacy: Selected Writings, American pedagogue Richard Chronister says that any lesson that doesn’t capitalize on this musical goal is cultivating a potential dropout.

Musical Understanding

Students who are taught by rote come to an early realization that music is composed with a logical structure. They learn rote pieces in larger pattern groups rather than one note at a time. They notice repeating ideas and variations of these ideas more easily when the distraction of reading the score is removed. Later on, having grasped patterns and structures by rote, students’ ability to see notation in patterns enhances their sight reading skill.

Memory

Students are comfortable with playing pieces by memory because this is the way they learn rote pieces. When students begin reading, they use their ears and memories in combination with their eyes to a much greater extent than students who are taught only by reading notation.

Concentration

Rote pieces enable students to learn pieces that are much longer than the average beginning reading piece. Due to this, rote pieces increase the ability of students to concentrate for longer periods of time. Rather than playing reading pieces that are only ten or twenty seconds long, they have the opportunity to play pieces that last a minute or two, often composed in variations or with more complicated form.

Creativity

Students are creative while improvising and composing because they have been exposed to a variety of sounds and patterns presented in rote pieces. The wide array of musical ideas in their ears, minds, and hands provide tools with which to invent their own music. Because beginning students often create at the piano by building on sounds and patterns to which they have already been exposed, the student who uses limited positions during his early lessons may not have the foresight to improvise and create in more sophisticated ways.

Technique

Students are free to focus on playing with proper technique when they are not simultaneously reading notation. For example, a teacher who is introducing a two-note slur can instruct the student to watch their hand for the down-up motion of the wrist. It is often difficult for an early level student to multitask, so the chance for success in mastering certain technical skills increases when the distraction of the score is removed.

Rhythm and Pulse

Most method books introduce only the longer rhythmic values at the beginning of study. This likely stems from the fact that young children do not learn fractions or subdivisions in school until later years. However, rote pieces are suited for introducing students to more complicated rhythms. These rhythms include subdivisions and syncopations, and are often more interesting to young children. Students have likely been exposed to these types of rhythms since birth by the music in their general environment, so they are able to execute the rhythms correctly by ear. This type of experience with rhythm will aid students when they read the corresponding notation at a later stage in their study.

Reading

Although it may seem counterintuitive, we have found that learning pieces by rote aids in the development of reading notation. Teaching by rote and teaching students to read notation do not need to be at odds. A combination of the two approaches is best, as this provides students with a well-rounded experience that will promote success in the many facets of playing the piano. When students play pieces learned by rote, they gain a repertoire of intervals, patterns, and technical motions in their muscle memory. When learning to read notation, this repertoire of patterns allows students to focus on what their eyes see rather than simultaneously having to acquire the new motions for their hands. Additionally, the understanding of pattern and form make it easier for students to decode reading pieces because they are able to see notes in larger pattern groups rather than simply reading one note at a time.

An interesting comparison to the rote vs. reading question is the debate in schools over teaching children to read phonetically or through the whole language method. Those who support phonics teach the sounds that make up words, and believe in a “part to whole” approach. Those who support whole language immerse the children in books and literature and hope they will learn to read in a more organic manner. In short, they believe in more of a “whole to part” philosophy. We can compare this to the way children learn the language of music. Students who learn by reading notes exclusively represent more of the “part to whole” approach, as opposed to those who learn by rote first. We contend that the best method is a blending of the two approaches: rote and reading presented simultaneously.

General Principles

- Rote teaching is ideally suited for use with students during the early stages of music study. This provides them with the opportunity to develop as musicians while taking the necessary time to build foundational reading skills.

- Rote pieces are at the student’s playing level, which is higher than their reading level at the beginning stage of study. The goal is that the student’s reading level will ultimately catch up with their rote playing level, but this may take a period of several years.

- Not every piece works well as a rote piece. Good rote pieces have patterns and form that are easily understood by beginners with limited theory knowledge, and they are designed to promote the benefits listed earlier in this article.

How to Successfully Teach a Rote Piece

- Generally speaking, it is important that students have a rote piece “in their ears” before learning it. Assign listening in the weeks prior to introducing a piece by rote.

- Engage the student’s imagination about the theme of the piece. Consider using props such as stuffed animals or adding a story to the piece.

- Design a movement activity that corresponds to the rote piece. This provides the opportunity for students to hear the piece again, and to experience it in their bodies.

- Break the piece up into manageable sections. These sections are often very short, sometimes only three or four notes. Demonstrate each section at the keyboard for the student as they closely watch you. The student imitates immediately afterward.

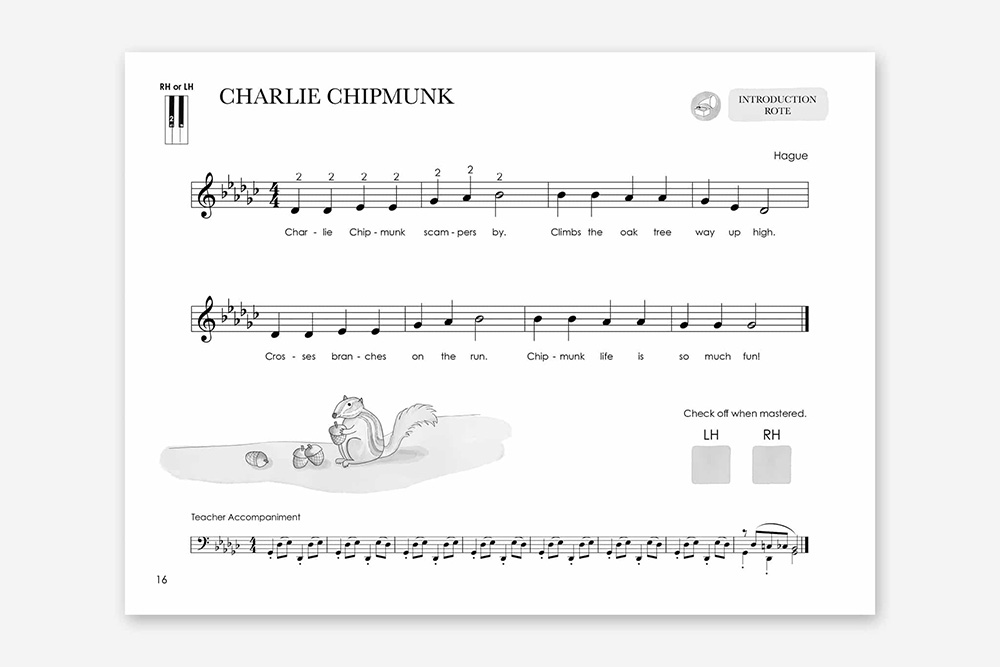

- Consider adding lyrics that describe the patterns in the piece. For example, in the rote piece Charlie Chipmunk, the teacher might sing, “Two times, two times, go-ing up,” to describe the opening two bars.

- Ask the student to repeat each section several times before adding sections together.

- Be sure the student has a way to remember the piece during the week at home between lessons. For example, you could create a “reminder video” or a mini tutorial for the piece, have the parent take notes, or draw a musical “map” of the patterns on a piece of paper. If the student is playing a rote piece from Piano Safari, reminder videos are available on the website in the Resources section.

Conclusion

Our goal in creating Piano Safari was to integrate the best features of all the piano methods we have used in our teaching. Combining aspects of rote teaching with intervallic reading provides, in our opinion, the most solid foundation for beginning piano students to become musical and literate pianists.